Labours of the Months

An Essay on Medieval Art and Agriculture by Peter Treherne

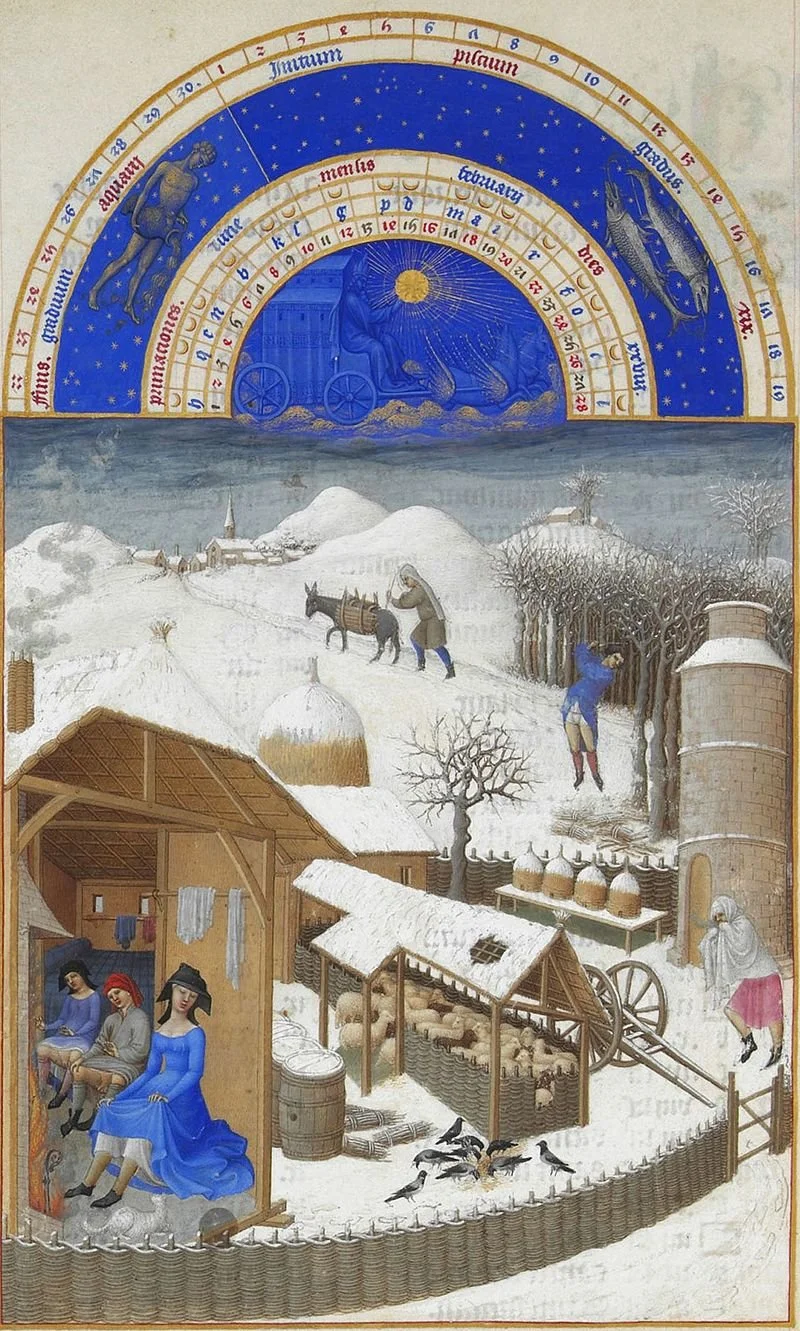

Jackdaws peck at grain in the snow. The snow is gone; the earth is grey and ploughed: a wooden mouldboard, a share, a ploughman in ragged grey, two oxen with tented hides. The first hay is mown, scythed in strips, raked into piles. Sheep unfold from fleeces. Blonde stooks, a hay cart, courtiers with peregrine falcons upon their arms. Peasants bend in water, hot from their harvesting.

These are labours of the months, medieval image-cycles depicting rural activities across the calendar year. Such cycles achieved special significance in books of hours – devotional aids mapping the Catholic faith onto the hours and days of medieval man. These illuminated labours have been traditionally interpreted as either Christian visions of harmony or as indicators of social oppression. Indeed, the vision of harmony might itself be a confirmation of peasant oppression. Many believe that the plight of the peasant is painted out of existence – they toil willingly, without a visible overlord, in clement conditions. Their existence as labourers on the land is elevated to the inevitable, to the universal – as inevitable and universal as the constellations above them. Thus the status quo is endorsed on a cosmic level.

But this reading fails to account for the corporeality and materiality of the images. The peasants of the Très Riches Heures – a book of hours from the early 15th Century – are far from universalised. A man, both hands raised to his mouth in a cataclysmic shiver, crosses an ice-cold farmyard. The ploughman, his ragged hose ripped at the knees, stumbles after oxen. Hay cutters hide from the oppressive sun beneath hats or veils. A sower, his face like melted and congealed wax, turns his back to a scarecrow as adequately clothed.

But the life of the peasant is not all hardship and drudgery. Greyed and bent by the water, peasants swim off the sweat of an August harvest whilst their noble counterparts canter like cut outs in the foreground. One peasant, splayed like a frog, displays his penis to the viewer. Another penis, worryingly horse-like, dangles beneath the breaststroke of a second peasant. The tone of this August image is uncertain – are these peasants deliberately debased to heighten the sophistication of the courtiers? Or do these frolickers in the water mock their noble masters? Maybe these momentary revellers, caught in sensual abandon, reveal the matter at stake in the foreground: a knight and a lady sit upon the same horse, and the gloved hand of the lady gently clasps the folds of the man’s cloak.

Whether socially subversive or affirmative, the Très Riches Heures considers the human form materially embedded within the environment. The peasants of August dive into the water because of the heat of the day, because of the heat of their labours. Three other peasants continue to work – one scythes, a second crouches to twine a sheaf, a third heaves sheaves into a wagon. These are the labours the peasants in the water rest from, and will return to. In September, the same contrast of rest and labour is performed. Four figures crouch, their backs painfully horizontal, and gather grapes from vines rising barely beyond their shins. Two other peasants stand in the foreground: the pregnant woman fixes her wimple that had, perhaps, unravelled as she bent over her full basket; the man, cross-eyed with pleasure, stuffs a grape into his mouth. These figures express an embodied and reciprocal relationship with the world. Their actions and endeavours, their momentary pleasures and pains, are bound up with the temperature, the weather conditions, the demands of agriculture.

Indeed, the labours contain narratives that combine human endeavour and the natural world. In October, a crop is sown. A man casts his seeds back and forth across recently ploughed furrows. Footprints stretch behind him, connecting him first to a sack of seeds and his drinking vessel, and then to a gathering of rooks and magpies that dip and peck at the fruit of his labour. Behind the birds comes the harrower astride his horse. His purpose is to cover the seeds, in part to protect them from the creatures that gobble up the precious grain. Between the horse and the harrow is a peppering of dung dropped moments before, which enriches the soil and provides necessary nutrients for the seeds that will, in Spring, be harvested for fodder, both for humans and animals. Behind the harrow sits a field already sown and harrowed and now crisscrossed with string and rags, and governed by a scarecrow with a bow – all attempts to frighten birds from feeding. This story of sowing unfolds across the painting, looping back and forth, from foreground to background, in the same way the sower and harrower must cross back and forth the fields of their labour. In this unfolding story, the peasants’ labour and the natural world conflict and collaborate. As mankind rests food from the barren earth, animals rob him and aid him. Weather conspires against him and provides all the necessary conditions for growth. This humdrum narrative of sowing, of human acts and natural events, stretches beyond October and binds each monthly task to an unending sequence in which the world and its inhabitants intermingle.

The historical development of books of hours is as embedded within the ever-changing environment as the labourers they portray. Initially based on a highly symbolic Roman tradition in which the seasons and months were represented through fixed and unchanging figures, by the 12th Century the specific agricultural practices of every region informed the types and times of labours depicted in individual books of hours. Italian cycles were often one month in advance of their Northern European cousins. Wine growing regions would emphasise the production of grapes. Climatic shifts such as the Little Ice Age dictated changes in content in the 16th Century. This speaks to the entangled relationship between art, agriculture and the environment. The artist cannot be extricated from the climate, just as the sower cannot avoid the siege of rooks and jackdaws.

What of the owner of the book of hours? They too are bound in a specifically medieval and specifically material way to the operations of nature. Overhead wheel the zodiacal stars emblazoned in gold on blue: water poured from a jug, a goat emerging from a shell, two pike connected at the mouth, a ram, a bull, an embracing couple, a crab, a long-necked lion, a lady between two rushes, scales in balance, a scorpion, a centaur with bow bent. In the labours of the Très Riches Heures, a curved hemisphere pictures the presiding zodiacs of the month. Each semi-circle is subdivided, like the markings of a clock, and each subdivision indicates a phase of the moon in martyrological letters. These hemispheres of influence conclude with a Homo Signorum or a zodiacal man. A raging bull severs his neck. The twins sit in the crook of each arm. At his belly is the balance; at his knees, the sea goat; beneath his feet, two fish; upon his chest, the crab. The celestial parade that marched across each hemisphere of the labours can now be found emblazoned on the human body – each zodiac corresponds to a specific anatomical part. A physician would use the map of the zodiacal man, in unison with the zodiacs of each month, to guide the letting of blood, and to govern the balance of the body: yellow and black bile, blood and phlegm. So the movement of the heavens governs the body of the owner of the book of hours.

But why do these georgic, pagan scenes erupt from a manual of Catholic faith? Why, in the Très Riches Heures, are the labours and the zodiacs comparable in scale to the divine? A ploughing peasant is given the same space and attention as the Nativity of Jesus or the Judgement of Christ. It is as if the Catholic faith has been subsumed, or even consumed, by secular, material life.

If there is a Christian message, it is oblique. Through Edenic, rose-tinted glasses, the labours are proof of divine order. Healthy peasants tend to a perfect land, sufficiently watered and warmed to bring forth food. No deluges or droughts destroy the crops. When it snows, mankind is already at rest beside the hearth, feasting on their labours. They are stewards of a land that is a garden, a microcosm that draws together the harmony of the spheres and the humours of the body. But, paradoxically, agriculture is also a curse. God in judgement, before the gates of Eden, cast Adam and Eve into the wasteland: ‘cursed is the ground for thy sake; in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life’. Before was plenty. After is labour. Courtiers might ‘have shelter and ease in their fine manors’, but beyond and behind them are the peasants who ‘have hardship and toil, the wind and the rain in the fields.’ The eye of the artist, whether sympathetic to their plight or as reductive and repressive as the eye of an overlord, presents the peasant in an endless, Sisyphean labour.

Both sides of this Christian paradox of nature (the perfectly ordered versus the cursed and chaotic) point towards entangled creation. The movement of the spheres, the changes in climate, the fluctuations of weather and the acts of animal life are imbricated and intermingled. Mankind cannot be unravelled from these wider forces. Agriculture and art cannot be unravelled from these wider forces. Not then, not now.

Labours of the Months in Très Riches Heures